STDs Links

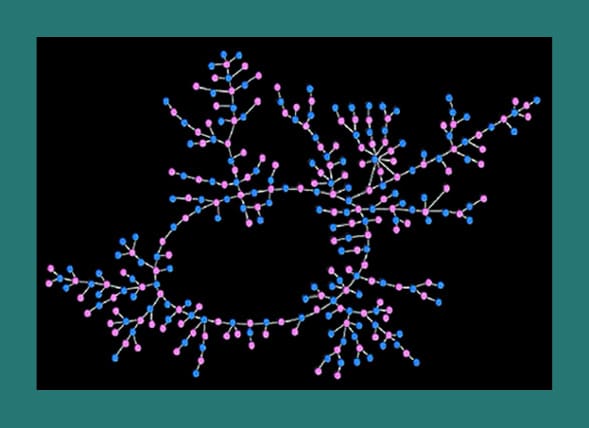

What you’re looking at is a sexual exposure map. To create it, scientists from Ohio State University tracked the sexual activity of an unnamed public high school in the Midwest. Their findings were published in the July 2004 issue of American Journal of Sociology.

What you’re looking at is a sexual exposure map. To create it, scientists from Ohio State University tracked the sexual activity of an unnamed public high school in the Midwest. Their findings were published in the July 2004 issue of American Journal of Sociology.

832 of the approximately 1000 students were interviewed, and asked to identify their romantic sexual partners over the past 18 months. A “romantic sexual partner” was defined as someone you were dating, and therefore mere “hook ups” were not included in the research. The research also did not include partners from other schools.

Here’s what they found: 573 students admitted to having at least one romantic sexual partner in the last 18 months. Of these 573 students, more than half could be traced to a network of 288 partners! (See image) The pink dots represent actual high school girls, and the blue represents the boys. The lines between them represent the links of sexual activity. As you can see, while a guy may have only one sexual partner, theoretically he could be connected to 286 sexual partners other than his own. In fact, the furthest two people on the map are separated by 37 steps. Surely, not one student in this map would have suspected this intricate web of sexual exposure, or the massive implications this has on STD transmission.

The above image does not include the other 285 students who had been sexually active. These students were involved in numerous and separate smaller networks.

What can be learned from this is that a person who has had only one sexual partner may sometimes be more at risk to acquire an STD than a person who has had multiple sexual partners, but is in a smaller sexual network. It also explains the rampant transmission of STDs among adolescents, and the dire need for chastity education.

In the 1960s gonorrhea and syphilis seemed to be the only well known STDs, and both of these could be treated with penicillin. Today there are over twenty-five different STDs, and some of the most common ones are without cures.[1] Among the STDs that can be cured, some are becoming increasingly resistant to modern antibiotics.

Most people who have an STD are unaware of their infection and contagious state.[2] This should especially alarm young people, because of the nineteen million new STD infections each year, nearly half of them are among people between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four.[3] According to the Centers for Disease Control, the direct medical cost associated with STDs in the United States is $14.1 billion each year![4]

Some of the most common STDs include HPV, chlamydia, herpes, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis. The four STDs that are incurable are HPV, HIV, herpes, and hepatitis. All of the others can be cured.

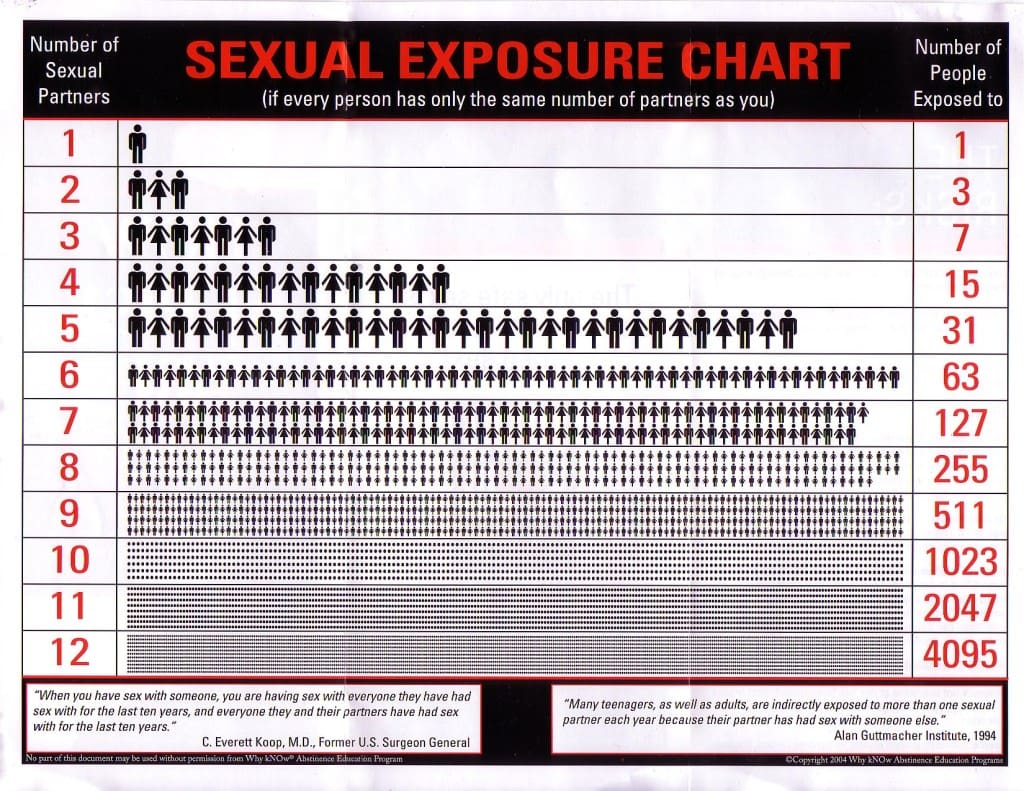

When considering the potential impact of STDs, we should remember the words of former U.S. Surgeon General C. Everett Koop: “When you have sex with someone, you are having sex with everyone they have had sex with for the last ten years, and everyone they and their partners have had sex with for the last ten years.”[5] Further, people can get tested for STDs, be told that they are clean, and then transmit dormant STDs the tests did not detect. Most tests today pick up the majority of the infections they are testing for. The problem is that many people believe they have been tested for all STDs when, in reality, they have been tested for only a few.

Recently a high school girl contacted me because she was considering sleeping with her boyfriend. She was a virgin, but he had been with eleven girls. If his previous partners were as sexually active as he had been (and depending on the types of STDs), she could be exposing herself to the possible infections of more than two thousand people if she slept with him once.[6] Wisely, she chose not to take the risk.

__________________________

[1]. R. Eng and W.T. Butler, The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1997), 1.

[2]. Joe McIlhaney, M.D., Safe Sex (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker House Books, 1992), 23.

[3]. Hillard Weinstock et al., “Sexually Transmitted Diseases Among American Youth: Incidence and Prevalence Estimates, 2000,” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 36:1 (January/February 2004), 6–10.

[4]. Centers for Disease Control, “Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2005,” Division of STD Prevention (December 2006), 1.

[5]. C. Everett Koop, M.D., as quoted by “Safe Sex?” (Boise, Idaho: Grapevine Publications, 1993).

[6]. Sexual Exposure Chart

Women are more susceptible to STDs than men because of the nature of their reproductive organs. Many STDs survive best where it is dark, moist, and warm. Because the woman’s reproductive system is mostly interior, her body is more easily infected. Compared to a man, she also has a larger surface area of tissue that certain STDs might affect. Furthermore, a woman’s body is exposed to infectious diseases for a longer amount of time after intercourse. These biological differences make women more likely to catch certain STDs.

The risk of infection is greater for young women because the cervix of a teenager is immature. In what is known as the “transformation zone” of her cervix, young women have what is called “cervical ectopy.” This means that the cells from within the cervical canal extend out toward the opening of the cervix. Such cells are sensitive to infections, and so their exposure makes the women more vulnerable to certain STDs. The rapid cell changes within the cervix also make a young woman more susceptible to certain diseases. When a woman reaches her mid-twenties, the cervix will have matured and some of its tissue been replaced by a different type that is more resistant to infections from STDs.[1]

The birth control pill also increases a young woman’s chance of contracting certain STDs because it interferes with her immune system.[2] The Pill also causes the production of a certain type of cervical mucus that makes it easier for cancer-causing agents to have access to a woman’s body.[3] All this research only confirms the fact that a woman’s body is like her heart: she is not designed for multiple sexual partners. She is made for love.

__________________________

[1]. R. Eng and W. T. Butler, The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1997), 71–73; “Pelvic Inflammatory Disease,” Fact Sheet (CDC); A.B. Moscicki, et al., “Differences in Biologic Maturation, Sexual Behavior, and Sexually Transmitted Disease Between Adolescents with and without Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia,” Journal of Pediatrics 115:3 (September 1989): 487–493; A.B. Moscicki, et al., “The Significance of Squamous Metaplasia in the Development of Low Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions in Young Women,” Cancer 85:5 (1 March 1999): 1139 –1144; M.L. Shew, et al., “Interval Between Menarche and First Sexual Intercourse, Related to Risk of Human Papillomavirus Infection,” Journal of Pediatrics 125:4 (October 1994): 661–666; Vincent Lee, et al., “Relationship of Cervical Ectopy to Chlamydia Infection in Young Women,” Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 32:2 (April 2006): 104–106.

[2]. G. Yovel, et al., “The Effects of Sex, Menstrual Cycle, and Oral Contraceptives on the Number and Activity of Natural Killer Cells,” Gynecologic Oncology 81:2 (May 2001), 254–262; M. Blum, et al., “Antisperm Antibodies in Young Oral Contraceptive Users,” Advances in Contraception 5 (1989), 41–46; C.W. Critchlow, et al., “Determinants of Cervical Ectopia and of Cervicitis: Age, Oral Contraception, Specific Cervical Infection, Smoking, and Douching,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 173:2 (August 1995), 534–43; J.M. Baeten, et al., “Hormonal Contraception and Risk of Sexually Transmitted Disease Acquisition: Results from a Prospective Study,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 185:2 (August 2001), 380–385; Catherine Ley, et al., “Determinants of Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection in Young Women,”Journal of the National Cancer Institute 83:14 (July 1991), 997–1003; M. Prakash, et al., “Oral Contraceptive Use Induces Upregulation of the CCR5 Chemokine Receptor on CD4(+) T Cells in the Cervical Epithelium of Healthy Women,” Journal of Reproductive Immunology 54:1–2 (March 2002), 117–131; C.C. Wang, et al., “Risk of HIV Infection in Oral Contraceptive Pill Users: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 21:1 (May 1999), 51–58; L. Lavreys, et al., “Hormonal Contraception and Risk of HIV-1 Acquisition: Results From a 10-Year Prospective Study,” AIDS 18:4 (March 2004), 695–697; W.C. Louv, et al., “Oral Contraceptive Use and the Risk of Chlamydial and Gonococcal Infections,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 160:2 (February 1989), 396–402; J.A. McGregor and H.A. Hammill, “Contraception and Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Interactions and Opportunities,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 168:6:2 (June 1993), 2033–2041.

[3]. John B. Wilks, A Consumer’s Guide to the Pill and Other Drugs, 2nd ed. (Stafford, Va.: American Life League, Inc., 1997), 30.

You should get tested as soon as possible, and since testing can usually be done on a confidential basis, it is not necessary to go with your parents. To find a clinic in your area, you could call 800-762-2296 or click here. Or you could call a local crisis pregnancy center or hospital, and they can refer you to a clinic for testing.

Regarding your parents: You may think, “What Mom and Dad don’t know can’t hurt them. If I did tell them, my mom would cry for a week, and I would probably be grounded until I’m 40.” As difficult as this may be, put yourself in your parents’ shoes. Imagine you had a child who was sexually active. You would want your child to be able to come to you and be honest about whatever was going on in his or her life.

The sooner you get a real relationship with your folks, the better. Sure, your parents will be upset, but under that hurt are two hearts that want only what is best for you. Some teens shut their parents out of their lives because of pride. If they had listened to their parents in the first place, they would have avoided so many mistakes. Swallow your pride, and do what you would want your own child to do. Even if you refuse to tell them, make sure to get tested. Some STDs can be easily cured but may lead to infertility or even more serious consequences if they are not treated.

Some of the symptoms of STDs include blisters, warts, lesions, painful urination, itching, swelling, and unnatural bleeding or discharge. However, many STDs have no obvious symptoms, and eight out of ten people who have an STD are currently unaware of their infection.[1] If you have had any genital contact, you should get tested. Many STDs may remain dormant and undetectable for some time, so you could test negative for STDs and still be infected. This is why clinicians recommend that women (and some men) who have been sexually active in the past get tested annually, regardless of their current sexual activity.

Doctors administer different tests to determine the presence of an STD, depending upon the person’s symptoms and sexual history. If you have ever had intercourse, you should receive all of the following tests: 1) Pap test (for women) and perhaps HPV screening by means of an HPV DNA detection test; 2) cervical cultures for gonorrhea and chlamydia (for women); 3) vaginal swabs for trichomonas and bacterial vaginitis (for women); 4) culture of any ulcers or sores (herpes and syphilis); 5) blood tests for HIV, hepatitis profile, and syphilis.[2] You may also be tested for other infections by means of a urine sample. Oral (and anal) sex can transmit virtually every STD,[3] and hand-to-genital contact can transmit some as well.[4] Therefore, even virgins can get STDs, including oral cancer from HPV.[5]

When one STD is diagnosed or suspected, there are likely to be more. Since some STDs can lead to sterility in men and women—and even death—you should treat any possible STDs as soon as possible. For a free, anonymous, and helpful tool for STD diagnosis, click here.

____________________

[1]. Joe McIlhaney, M.D., Safe Sex (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker House Books, 1992), 23.

[2]. Sex is a Choice. Be Informed (Grand Rapids, Michigan: The Core-Alliance Group, Inc., 2000).

[3]. Medical Institute for Sexual Health, Sex, Condoms, and STDs, 28; B. Dillon, “Primary HIV Infections Associated with Oral Transmission,” CDC’s 7th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Abstract 473, San Francisco, February 2000; Centers for Disease Control, “Transmission of Primary and Secondary Syphilis by Oral Sex—Chicago, Illinois, 1998–2002,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 51:41 (22 October 2004): 966–968.

[4]. Rachel Winer, et al., “Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection: Incidence and Risk Factors in a Cohort of Female University Students,” American Journal of Epidemiology 157:3 (2003): 218–226; Sepehr Tabrizi, et al., “Prevalence of Gardnerella Vaginalis and Atopobium Vaginae in Virginal Women,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 33:11 (November 2006): 663–665; C. Sonnex, et al., “Detection of Human Papillomavirus DNA on the Fingers of Patients with Genital Warts,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 75 (1999): 317–319.

[5]. A. Frega, et al., “Human Papillomavirus in Virgins and Behaviour at Risk,” Cancer Letters 194:1 (8 May 2003): 21–24; Gypsyamber D’Souza, et al., 1944–1956; Hammarstedt, et al., 2620–2623; Justine Ritchie, et al., 336–344; Herrero, et al., 1772–1783.

Chlamydia is the most commonly reported infectious disease in the United States. It is caused by the bacterium chlamydia trachomatis. In 2005 nearly a million cases were reported, but most cases go undiagnosed, and so the CDC estimate that about three million infections occur each year in the United States.[1] The disease is found primarily among teenage girls and young women. In fact, nearly three out of every four cases of chlamydia in women are found in girls between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four.[2] It is estimated that 40 percent of sexually active single women have been infected at some time with chlamydia.[3] (However, since the disease is curable, this does not mean that 40 percent of women are currently infected.) The disease is so common that there are more cases of chlamydia reported than all cases of AIDS, chancroid, gonorrhea, hepatitis (types A, B, and C), and syphilis combined![4] This STD can also be spread by means of oral sex.[5] Some of the symptoms of genital chlamydial infection include vaginal or urethral discharge, burning with urination, pelvic pain, and genital ulcers. Men can experience many of these symptoms, and also tenderness of the scrotum. In many cases the man will experience no symptoms, despite the fact that the STD can damage his fertility.[6] Sometimes a chlamydial infection can lead to sterility in men, although this is not common.

As is the case with most STDs, women are more likely to suffer serious consequences of chlamydial infection. For example, chlamydia may spread to a woman’s uterus and fallopian tubes, causing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). This can lead to infertility and may become a life-threatening infection. One way it can be deadly is by increasing a woman’s risk of having an ectopic pregnancy, where the newly conceived baby implants outside of the uterus. One reason this can happen is that PID can scar the fallopian tubes, making it more difficult for a newly conceived baby to be transferred through them to the womb. If the baby gets stuck in one of the tubes and the condition is not treated, it can be fatal for the mother because the fallopian tube can burst.

Ectopic pregnancies account for less than 2 percent of all pregnancies, and the vast majority of these women survive. But the complications that can arise from the condition make it the leading cause of maternal death in the first trimester of pregnancy.[7] Each year more than a million American women experience PID.[8] According to the CDC, “Up to 40 percent of females with untreated chlamydia infections develop PID, and up to 20 percent of those may become infertile.”[9] Unfortunately, most women (and half of men) who are infected with chlamydia show no symptoms.[10] Consequently they may not receive treatment with the necessary antibiotics.

Additionally, the screening test for chlamydia may miss the infection, and the woman can be given what is called a “false negative” diagnosis. In other words, she is told that she does not have chlamydia, despite the fact that she is infected.[11] Even when diagnosed accurately, the antibiotics prescribed may stop the bacteria from reproducing, but the disease may reactivate later. Years after the initial infection, the disease can still be present in the woman’s fallopian tubes, without symptoms.[12]

Even when the disease is treated, its effects may linger. While in a woman’s body, chlamydia causes the production of heat shock protein (HSP). Especially when a woman has a prolonged chlamydial infection without knowing it, her immune system creates antibodies against the HSP. This means that her white blood cells learn to attack HSP, because they associate it with chlamydia. If the woman becomes pregnant, this creates a problem. One of the first proteins made by an embryo is a type of HSP similar to the one made by chlamydia. Because the chlamydial infection trained her immune system to be hostile to HSP, her immune system may react against her baby. This can interfere with the development of the embryo. It can also leave the embryo less protected, making the unborn child more likely to die before implanting in the uterus.

Finally, it can create an inflammatory reaction in the uterus. This may cause a “spontaneous abortion” or miscarriage.[13] In one study of 216 women with infertility problems, 21 percent of them tested positive for chlamydial HSP antibodies, despite the fact that none of them knew that they had ever been infected.[14] Larger studies of women with fertility problems estimate that between 30 and 60 percent of them have chlamydia antibodies in their serum (blood plasma), indicating that they had been infected with chlamydia at some point in the past.[15] A teenager may contract chlamydia, never show symptoms of the infection, and then experience fertility problems ten years later when she and her husband try to conceive a baby. For all of these reasons chlamydia is called the “silent sterilizer.”

Because of the physical nature of STDs, the emotional consequences of the infections are often overlooked. One woman said, “Sometime during my wild college days, I picked up an infection that damaged the inside of my fallopian tubes and left me infertile. I am now married to a wonderful man who very much wants children, and the guilt I feel is overwhelming. We will look into adoption, but this whole ordeal has been terribly difficult.”[16] Should a woman contract chlamydia and conceive successfully, it is possible for her to pass the infection on to her baby. This can lead to blindness, pneumonia, or premature birth.[17] Even when a woman receives treatment for chlamydia, doctors are encouraged to follow up with her three months later.[18] This is because many girls get reinfected from their untreated partner(s).

Because of how the disease compromises a woman’s immune system, women with chlamydia are up to five times as likely to become infected with HIV, if exposed,[19] and are more likely to develop cervical cancer from HPV.[20] One rare form of chlamydia is known as Lymphogranuloma Venereum (LGV). This disease may cause a person’s lymph nodes in the groin to swell up to the size of a lemon and burst. LGV is not nearly as common as chlamydia, but it has been detected especially in people who engage in high-risk sexual behaviors.

Consistent and correct condom use may reduce (but not eliminate) the risk of being infected with chlamydia, but the degree of protection offered by the condom is not certain. According to the most comprehensive research on condom effectiveness for STD prevention, the National Institutes for Health reported, “Taken together, the available epidemiologic literature does not allow an accurate assessment of the degree of potential protection against chlamydia offered by correct and consistent condom usage.”[21] Since the time of this report, other studies have suggested that condom use may decrease the risk of chlamydia infections by about half.[22]

________________________

[1]. “Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2005,” 1.

[2]. “Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases,” 2.

[3]. Joe McIlhaney,M.D., Safe Sex (Grand Rapids,Mich.: BakerHouse Books, 1992), 103.

[4]. Medical Institute for Sexual Health, “Sexual Health Update,” 7:2 (Summer 1999), 1.

[5]. S. Edwards and C. Carne, “Oral Sex and Transmission of Non-Viral STIs,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 74:2 (April 1998), 95–100.

[6]. S. S. Witkin, et al., “Relationship Between an Asymptomatic Male Genital Tract Exposure to Chlamydia Trachomatis and an Autoimmune Response to Spermatozoa,”Human Reproduction 11 (November 10, 1995), 2952–2955; R. Gdoura, et al., “Chlamydia Trachomatis and Male Infertility in Tunisia,” The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care 6:2 (June 2002), 102–107; A.A. Pacey and A. Eley, “Chlamydia Trachomatis and Male Fertility,” Human Fertility 7:4 (December 2004), 271–276.

[7]. Tatiana Goldner, et al., “Surveillance for Ectopic Pregnancy—United States, 1970–1989,” MMWR Weekly 42:SS-6 (December 17, 1993) 73–85; “Current Trends Ectopic Pregnancy—United States, 1990–1992,” Centers for Disease Control, MMWR Weekly 44:3 (January 27, 1995), 46–48.

[8]. Centers for Disease Control, “Pelvic Inflammatory Disease,” Fact Sheet (May 2004).

[9]. “Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2005,” 1.

[10]. “Tracking the Hidden Epidemics, Trends in STDs in the United States 2000,” CDC, 6.

[11]. Jolande Land, et al., “Chlamydia Trachomatis in Subfertile Women Undergoing Uterine Instrumentation,” Human Reproduction 17:3 (March 2002), 526.

[12]. Land, et al., 525–527; S.D. Spandorfer, “Previously Undetected Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection, Immunity to Heat Shock Proteins and Tubal Occlusion in Women Undergoing In-Vitro Fertilization,” Human Reproduction 14:1 (January 1999), 60–64; J. Debattista, et al., “Immunopathogenesis of Chlamydia Trachomatis Infections in Women,” Fertility and Sterility 79:6 (June 2003), 1273–1287.

[13]. S. S. Witkin, et al., “Unsuspected Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection and In Vitro Fertilization Outcome,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 171:5 (November 1994), 1208–1214; A. Neuer, et al., “The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Reproduction,” Human Reproduction Update 6:2 (2000), 149–159; S. S. Witkin, et al., “Immune Recognition of the 60kD Heat Shock Protein: Implications for Subsequent Fertility,” Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 4 (1996), 152–158; A. Neuer, et al., “Humoral Immune Response to Membrane Components of Chlamydia Trachomatis and Expression of Human 60 kDa Heat Shock Protein in Follicular Fluid of In-Vitro Fertilization Patients,” Human Reproduction 12:5 (1997), 925–929; A. Neuer, et al., “Heat Shock Protein Expression during Gametogenesis and Embryogenesis,” Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology 7 (1999), 10–16.

[14]. A. Neuer, et al., “The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Reproduction,” Human Reproduction Update 6:2 (March/April 2000), 149–159.

[15]. Land, et al., 525–527; C.M. J. Mol, et al., “The Accuracy of Serum Chlamydial Antibodies in the Diagnosis of Tubal Pathology: A Meta-Analysis,” Fertility and Sterility 67:6 (June 1997), 1031–1037.

[16]. Thomas Lickona, “The Neglected Heart: The Emotional Dangers of Premature Sexual Involvement” (January 2007), 11.

[17]. “Tracking the Hidden Epidemics,” 4.

[18]. Centers for Disease Control, “2006 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines” (September 2006).

[19]. “Chlamydia,” fact sheet, CDC.

[20]. F.X. Bosch, et al., “Chlamydia Trachomatis and Invasive Cervical Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of the IARC Multicentric Case-Control,” International Journal of Cancer111:3 (September 1, 2004), 431–439.

[21]. National Institutes of Health, “Workshop Summary: Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention,” 17.

[22]. Ahmed S, et al., “HIV Incidence and Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevalence Associated with Condom Use: A Population Study in Rakai, Uganda,” AIDS 15:16 (2001), 2171–2179; J. Baeten, et al., “Hormonal Contraception and Risk of Sexually Transmitted Disease Acquisition: Results from a Prospective Study,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 185:2 (2001), 380–385.

Gonorrhea is the second most commonly reported infectious disease in the United States.[1] According to the CDC, “African-Americans remain the group most heavily affected by gonorrhea, with a rate in 2005 that was eighteen times greater than the rate for whites.”[2] Worldwide, about sixty-two million cases occur each year.[3]

Gonorrhea is highly contagious, especially for women. Through a single act of intercourse with an infected partner, the male has a 20 percent chance of contracting it from an infected female, but the female has about a 70 percent chance of being infected from a man who has the disease.[4] When a person is infected with one STD, it often makes his or her body more likely to be infected with others. In the case of gonorrhea, the infected person is three to five times as likely to get HIV if exposed.[5] Furthermore, men with a history of gonorrhea are twice as likely to develop bladder cancer.[6]

When a person is infected, his or her symptoms vary, depending upon the individual and what part of the body is infected. Some experience a discharge from the genitals and painful urination. Women can suffer from abnormal bleeding, and men from swelling around the testicles. This may be a sign of epididymitis in the male, a condition that can lead to infertility if not treated. In a woman, gonorrhea may spread to the uterus and fallopian tubes, leading to Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID), which can cause infertility. Infected mothers may also pass the disease to their babies during birth, which can lead to blindness, joint disorders, and a life-threatening blood infection in the child. However, if a woman receives treatment for gonorrhea, she can reduce the risk of infecting her baby.

The majority of infected men will show symptoms of the disease within days of contracting it. However, many women will experience no initial symptoms.[7] For men and women alike, the disease can remain undetected even though the person’s mouth may be infected. If the disease is detected, it can be treated with antibiotics.

Doctors have noticed, however, that gonorrhea is becoming increasingly resistant to the antibiotics used to treat it. One specialist remarked, “Gonorrhea has now joined the list of other superbugs for which treatment options have become dangerously few.”[8] According to the CDC, “Resistance is especially worrisome among men who have sex with men (MSM), where resistance was nearly eight times higher than among heterosexuals (29 percent vs. 3.8 percent).”[9]

Gonorrhea can be transmitted by means of intercourse, oral sex, and anal sex. The National Institutes of Health reported that condom use reduces the risk of gonorrhea for men. But “the available epidemiologic literature does not allow an accurate assessment of the degree of protection against gonorrhea infection in women offered by correct and consistent condom use.”[10] Studies published since the NIH report estimate that the condom can reduce the risk of gonorrhea by about half.[11] Therefore, even correct and consistent condom use does not eliminate the risk of contracting the disease.

The findings are especially dismal for those who report inconsistent condom use. According to one medical journal, “Inconsistent condom use was not protective against HIV and STDs, and significantly increased the risks of infections such as gonorrhea and chlamydia. Inconsistent condom use may actually be an ‘enabling’ process allowing individuals to persist in high-risk behaviors with a false sense of security.”[12] This study is not the only one to show that those who use condoms less than perfectly are more likely to contract STDs than those who do not use condoms at all.[13]

The reason for this, as the journal explained, is that those who report condom use may be more likely to engage in risky behavior (such as having multiple sexual partners). According to one researcher, “The number-one determinant of whether a person will catch a sexually transmitted disease is the number of lifetime sexual partners. We seem to go out of our way as a government and a nation to avoid telling people that, but we hand out a lot of free condoms.”[14]

____________________________

[1]. Centers for Disease Control, “Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2005,” Division of STD Prevention (December 2006), 3.

[2]. “Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases,” 3.

[3]. National Institutes of Health, “Workshop Summary: Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention.”

[4]. National Institutes of Health, “Workshop Summary.”

[5]. D.T. Fleming and J.N. Wasserheit, “From Epidemiological Synergy to Public Health Policy and Practice: The Contribution of Other Sexually Transmitted Diseases to Sexual Transmission of HIV Infection,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 75 (1999), 3–17.

[6]. D. S. Michaud, et al., “Gonorrhoea and Male Bladder Cancer in a Prospective Study,” British Journal of Cancer 96 (2007), 169–171.

[7]. National Institutes of Health, “Workshop Summary: Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention.”

[8]. Rob Stein, “Drugs Losing Efficacy Against Gonorrhea,” Washington Post (April 13, 2007), A03.

[9]. “Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases,” 4.

[10]. National Institutes of Health, “Workshop Summary,” 16.

[11]. Ahmed S, et al., “HIV Incidence and Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevalence Associated with Condom Use: A Population Study in Rakai, Uganda,” AIDS 15:16 (2001), 2171–2179; J. Baeten, et al., “Hormonal Contraception and Risk of Sexually Transmitted Disease Acquisition: Results from a Prospective Study,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 185:2 (2001), 380–385.

[12]. Ahmed, et al., 2177.

[13]. T.K. Young, et al., “Factors Associated with Human Papillomavirus Infection Detected by Polymerase Chain Reaction Among Urban Canadian Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Women,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 24:5 (May 1997), 293–298; L. Manhart, L. Koutsky, “Do Condoms Prevent Genital HPV Infection, External Genital Warts, or Cervical Neoplasia? A Meta-Analysis,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29:11 (2002): 725–735.

[14]. Robert E. Rector, Heritage Foundation, in Avram Goldstein, “District to Offer Condoms for Free,” Washington Post (December 2, 2003), B01.

Herpes is a virus that infects the skin and mucous membranes such as the mouth and genitals. Herpes type one (HSV-1) infects 58 percent of people and primarily causes oral infections, such as cold sores.[1] Most people with HSV-1 do not have it as a result of sexual contact. However, it can be transmitted to and from the genitals by means of oral sex. Due to the increasingly common practice of oral sex, certain populations—such as high school and college students—are seeing a steep increase in genital HSV-1 infections.[2] Type two (HSV-2) mostly causes genital herpes, and it also can be transferred to the mouth from the genitals.

Unlike certain STDs that are spread only by means of bodily fluid, herpes is most often spread by skin-to-skin contact. Not only a person’s genitals but also his or her abdomen, thighs, hands, and other areas can be infected. Herpes can be picked up through contact with these areas and transmitted by a partner who shows no symptoms.

Since herpes is easily transmitted and incurable, it is the most common STD in terms of the number of individuals currently infected. In other words, it is the most prevalent STD. While it is unknown how many people are infected with genital HSV-1, about one in six people are infected with genital HSV-2.[3] Among sexually active singles, the percentage of those infected with herpes is even higher: between 30 and 40 percent![4] While these numbers may seem astoundingly high, one must realize that nine out of ten people who have genital herpes are unaware that they are infected.[5] This is especially worrisome since people with herpes are at an increased risk of contracting and spreading HIV.[6] Women with HSV are also more susceptible to cervical cancer from HPV.[7]

Within a week of contracting herpes, a person may have preliminary symptoms including fever, headache, and muscle aches. Lesions may then appear where the virus was contracted. The lesions usually begin as small blisters before breaking and becoming ulcers. Other symptoms include itching, burning with urination, vaginal discharge, and swollen lymph nodes in the groin area. Since herpes is incurable, it is not uncommon for infected people to have recurrent outbreaks of lesions for the rest of their lives.

Thankfully, it is uncommon for a mother to pass the virus on to her newborn child. But if this occurs, it can be fatal for the baby. To avoid such a tragedy, women with active herpes infections usually give birth by means of a caesarean delivery.[8] Although there is no cure for herpes, antiviral medications can shorten and sometimes prevent outbreaks.

Regarding prevention of the virus, studies show that if a person uses a condom consistently and correctly, it will decrease the risk of herpes transmission by only about half.[9] Therefore, do not expect a condom to protect you or your future spouse and children from the effects of this STD.

_______________________________

[1]. Fujie Xu, et al., “Trends in Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and Type 2 Seroprevalence in the United States,” Journal of the American Medical Association 296:8 (August 2006), 964–973.

[2]. C.M. Roberts, et al., “Increasing Proportion of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 as a Cause of Genital Herpes Infection in College Students,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases30:10 (October 2003), 797–800; G. B. Lowhagen, et al., “First Episodes of Genital Herpes in a Swedish STD Population: A Study of Epidemiology and Transmission by the Use of Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) Typing and Specific Serology,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 76 (2000), 179–182; Mary Jo Groves, “Transmission of Herpes Simplex Virus Via Oral Sex,” American Family Physician 73:7 (April 2006), 1527–1534.

[3]. Fujie Xu, et al., 964–973.

[4]. Joe McIlhaney,M.D., Safe Sex (Grand Rapids,Mich.: BakerHouse Books, 1992), 100.

[5]. D.T. Fleming, et al., “Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 in the United States, 1976 to 1994,” The New England Journal of Medicine 337 (October 16, 1997), 1105–1111; P. Leone, “Type-specific Serologic Testing for Herpes Simplex Virus-2,” Current Infectious Disease Reports 5:2 (April 2003), 159–165.

[6]. Fujie Xu, et al., 964–973.

[7]. J. S. Smith, et al., “Herpes Simplex Virus-2 as a Human Papillomavirus Cofactor in the Etiology of Invasive Cervical Cancer,” Journal of the National Cancer Institute94:21 (November 6, 2002), 1604–1613.

[8]. Centers for Disease Control, “Genital Herpes,” Fact Sheet (May 2004).

[9]. J.C. Shlay, et al., “Comparison of Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevalence by Reported Level of Condom Use Among Patients Attending an Urban Sexually Transmitted Disease Clinic,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 31:3 (March 2004), 154–160; Anna Wald, et al., “The Relationship Between Condom Use and Herpes Simplex Virus Acquisition,” Annals of Internal Medicine 143:10 (2005), 707–713.

There’s a short answer and a long one for your question. The simple answer is because condoms don’t offer adequate protection from HPV.

The long answer is much more complex. For one, the information on condom warning labels is “enforced” by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). They’re the ones who are supposed to make sure that the information is medically accurate. So, why don’t they tell you that the condom doesn’t protect against HPV? It’s a messy story:

In 1999, the director of the National Cancer Institute reported to Congress that “Condoms are ineffective against HPV” and that “additional research efforts by NCIL on the effectiveness of condoms in preventing HPV transmission are not warranted.”[1]

On October 3, 2000, the “Cervical Cancer Public Awareness Resolution” was presented before the US House of Representatives. In it, Congressman Tom Coburn, who had a full-time practice in obstetrics and family medicine, said, “Along with that comes the very sad fact that our institutions that we should be trusting in this area have failed us. The Center for Disease Control has failed, because the full name of the Center for Disease Control is the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The NIH has released a statement, as well as NCI, and on their Web site you can find that this disease is caused by human papilloma virus and that a condom fails to protect. We are so sold on this concept of ‘safe sex’ in this country that we refuse to accept the etiology and pathogenesis of this disease, and we refuse to be honest with the American public in that a condom cannot protect them from this. The thing that is exciting to me about this resolution coming up is it perhaps will have some honesty coming out of the institutions that are funded with the taxpayers’ money in this country, both the NIH and the NCI, as well as the CDC.”[2]

Coburn added that they had a breast and cervical cancer treatment bill that was “being held up at this time on the basis of the Senate conferees not wanting to agree to the language in that in regards to HPV and cervical cancer.” He pleaded to the Speaker of the House, ” Mr. Speaker, I would like to ask the body that they would put pressure on their fellow Senators that they might accede to this. The fact is, the reason we have this awareness up is we want women to get treated. This is a disease that is absolutely curable. It is not like breast cancer; we cannot always cure breast cancer. This disease, if diagnosed properly and treated, is 100 percent curable. Knowledge and the fact that we are allowing a safe sex message of condoms preventing this disease to continue will do nothing but harm women….The fact is, it is harmful to women to let that lie continue.”

Later that year, the United States Congress approved Public Law 106-554. This law directed the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and FDA to educate the public about HPV. Part of the bill required that educational material regarding STDs like HPV shall “contain medically accurate information regarding the effectiveness or lack of effectiveness of condoms in preventing the STD the materials are designed to address.” The CDC was given until December 21, 2003 to issue a report “including a detailed summary of the significant findings and problems and best strategies to prevent future infections, based upon available science.”

December 21st came and went, and nothing was done. Indiana Representative Souder (the Chairman of the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy, and Human Resources), pressed them on it and they finally released the January 2004 report to Congress: “Prevention of Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection.” In it, the CDC admitted, “The available scientific evidence is not sufficient to recommend condoms as a primary prevention strategy [against HPV]”. However, it remains to be seen if the CDC will actually implement an effective public policy to inform Americans of this.

On February 12, 2004, Rep. Souder wrote a letter to the Commissioner of the FDA, Mark McClellan, M.D., Ph.D., asking him to re-examine the misleading information given on condom labels. In this letter, he reminded the FDA of the findings in the CDC report the previous month, and wrote, “A meta-analysis reviewing the best available data describing the relationship between condoms and HPV-related conditions’ from the past two decades published in the November 29, 2002 edition of the journal Sexually Transmitted Diseases found, ’There was no consistent evidence of a protective effect of condom use on HPV DNA detection, and in some studies, condom use was associated with a slightly increased risk for these lesions.’ Three years after Public Law 106-554 was signed by President Clinton, condom labels still do not warn consumers about the lack of protection against HPV infection. The Subcommittee urges FDA to act on the release of CDC’s HPV prevention report and immediately relabel condoms to alert consumers that condoms do not provide effective protection against HPV infection.”[3] However, Dr. McClellan remained the commissioner of the FDA for only a month after this letter was written, so not much was done under his watch.

Since then, the FDA has not done a great deal. They said that they’re “certainly committed to looking at this and making the requisite changes.”[4] They’ve added that they’re “preparing new guidance on condom labeling,” “exploring new opportunities to best inform condom users about important limitations of the device,” and “proposing to amend the classification regulations for condoms.”[5] In other words, condom labels still had not changed. Dr. Tom Coburn, who is a physician, congressman, and co-chairman of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV and AIDS said, “The FDA has been dragging its feet for three and a half years.”[6]

Opponents of abstinence education disagree with Coburn. For example, Henry Waxman (D- CA), argues “we want to be sure that we do not end up with an unintended effect of confusing people about the situations when condoms do work—in HIV transmission to name only one—and actually reduce their use.” Furthermore, he added, condom labels that “include information on HPV can result in so much information on such a small package that it reduces the effectiveness of any information.”[7] Waxman apparently thinks that self-control is an unrealistic option for human beings. He assumes that if people knew the truth about condoms, they’d just throw them away and continue having sex.

In June 2005, Senator Coburn placed a hold on President Bush’s nomination for a new federal drug agency chief, hoping it would force the FDA to enforce a federal condom labeling law that requires all condom packaging to warn consumers that condoms are not effective in preventing HPV. Then, in September 2006, President Bush asked National Cancer Institute Director Andrew von Eschenbach to serve as acting agency commissioner of the FDA. Prior to his confirmation hearing, Dr. Eschenbach was asked if he would ensure that condom labels would be updated. He displayed his familiarity with the ineffectiveness of the condom, and added that it may offer some risk reduction for HPV related diseases. He then added that in November of 2005, the FDA drafted a document with proposed language for a new condom label. As a result of this document, Eschenbach said, “FDA received roughly 400 comments on the proposed rule. Almost all comments suggested the proposed labeling language was confusing and difficult for consumers to understand. As a result, the Agency intends to undertake additional labeling comprehension studies to help insure that the final labeling recommendations issued by the Agency are understandable to users.”[8]

Regarding the proposed new condom labels, Senator Coburn remarked, “In the five years it took the FDA to implement this law, over 27 million Americans have become infected with HPV, over 50,000 women have been diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer, and nearly 20,000 women have died from the disease. Despite these tragic numbers, very few Americans are still not aware of HPV or its link to cervical cancer and the FDA seems to be content with providing inconclusive claims of effectiveness that may endanger women be providing a false security against cervical cancer.”[9]

In November of 2006 (six years after the law was created requiring medically accurate condom labels) nothing had changed. So, Senator Coburn requested an investigation by the Government Accountability office of the failure of the FDA in this matter. In it, he stated, “I am requesting that GAO investigate the failure of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to comply with the provision of the same law that requires the agency to ‘reexamine existing condom labels that are authorized pursuant to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to determine whether the labels are medically accurate regarding the overall effectiveness or lack of effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted diseases, including HPV.’ It has been six years since this law was signed and FDA has yet to issue guidance to ensure condom labels meet this criteria. As you noted in your letter, ‘Section 317P of the Public Health Service Act addresses human papillomavirus specifically.’ Yet, condom labels do not currently mention the lack of effectiveness of condoms in protecting against HPV infection, which has been conclusively documented over the past decade.”[10]

This battle has been raging for years, without ever garnering the attention of the liberal media. When the CDC report on HPV was released, among major media outlets, only the Washington Post mentioned anything about it. In August of 2001, groups representing over 10,000 doctors accused the CDC for covering up the government’s own research about condom infectiveness (in particular, the NIH report). In the statement, which was released by the Physicians Consortium, former Congressman Tom Coburn, M.D., Congressman Dave Weldon, M.D. and others, it stated that the CDC has “systematically hidden and misrepresented vital medical information regarding the ineffectiveness of condoms to prevent the transmission of STDs. The CDC’s refusal to acknowledge clinical research has contributed to the massive STD epidemic.”[11]

The Physicians Consortium claimed that the CDC not only failed to educate the public about their findings, but tried to conceal the paper and delay its release. They added that the CDC demanded revisions of the report in order to cause “unwarranted confusion and misinformation to what otherwise is a clear-cut repudiation of condom effectiveness.”

Despite knowing about HPV and condom ineffectiveness, the CDC remained quiet. In a NIH “Consensus Statement” on Cervical Cancer, it was reported that “The data on the use of barrier methods of contraception to prevent the spread of HPV…does not support this as an effective method of prevention.”[12] That was in 1996! The CDC’s silence has been so inexcusable that the Physicians Consortium held a Capitol building press conference calling for the resignation of the (then) Director of the CDC, Dr. Jeffrey P. Koplan. Odds are, you didn’t see that on the evening news.

Finally, in December of 2008, the FDA issued a new document that outlines how condom labels should be updated. It stated that the condom label should inform customers that “Latex condoms are intended to prevent pregnancy, HIV/AIDS, and other sexually transmitted infections.” You’ll notice that the language shifted away from the effectiveness of the condom to a vague assertion of what it’s “intended” to to. In order to read anything about HPV, you need to browse through the condom’s information packet, which admits, “Latex condoms are less effective against STIs such as Human Papillomavirus (HPV) and herpes. These STIs can also be spread by contact with infected skin that is not covered by the condom.”

______________________________________

[1]. Richard D. Klausner, M.D., Letter to the U.S. House Commerce Committee, February, 1999.

[2]. Cervical Cancer Public Awareness Resolution (House of Representatives – October 03, 2000) http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?r106:H03OC0-0045:

[3]. “Rep. Souder Asks FDA for Action on Condom & HPV Information Law,” abstinence.net (12 February 2004).

[4]. FDA official Daniel Schultz, as quoted in “Condom Labels Called Inadequate,” Sylvia Smith, Fort Wayne Gazette, March 12, 2004.

[5]. Emphasis mine

[6]. “FDA Weighs Condom Warning Label,” by Keith Powers, Family News, March 15, 2004.

[7]. Ilka Couto and Cynthia Dailard, “Wanted: A Balanced Policy and Program Response to HPV and Cervical Cancer,” The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy 2:6 (December 1999).

[8]. “Latest News: Andrew C. Von Eschenbach, M.D., Confirmation, Questions for the Record,” Abstinence Clearinghouse E-mail Update (September 9, 2006), reply to Question 14.

[9]. Press Release, “Dr. Coburn Says New FDA Condom Regulations Make Inconclusive, Exaggerated Claims About Condom Effectiveness,” coburn.senate.gov, Washington, D.C. (November 10, 2005).

[10]. Senator Tom A. Coburn, M.D., Letter to Gary L. Kepplinger, General Counsel, U.S. Government Accountability Office, Washington, DC 20548, (November 1, 2006).

[11]. Austin Ruse, “Physicians Groups Charge US Government with Condom Cover-up, “Friday Fax, Vol 4 (Aug 17, 2001) No 35 (see http://www.c-fam.org).

[12]. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement on Cervical Cancer, April 1–3, 1996.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common STD in the world, infecting more than 440 million people.[1] There are over one hundred different types of HPV, and about thirty to forty of them cause genital infections.[2] While most people who contract HPV will not suffer serious consequences from the virus, it does cause 99.7 percent of cervical cancer, and this kills approximately 288,000 women annually.[3] In the United States the annual death toll from cervical cancer is fewer than four thousand. The reason for the relatively low figure is that HPV is often treated before it leads to cervical cancer. Unfortunately, women in developing nations often lack adequate health care and routine Pap testing. Therefore they are much more likely to suffer the full consequences of the virus.

HPV can also cause genital skin cancer, which has killed more than thirty thousand people in the United States.[4] Finally, HPV can cause genital warts, but only 1 percent of sexually active people experience this symptom.[5] Unfortunately, the virus can impact the health of children born to infected mothers. For example, I know of parents who took their infant to the doctor because she had a sore throat. The doctor examined her and told the parents that the child had genital warts growing on her larynx. This condition, recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP), is uncommon but still infects over two thousand children each year.[6] Since there is no cure for HPV, children with RRP often require laser surgeries to remove the warts. Sadly, the average child with RRP needs surgery every three months for several years; such a child will have more than twenty surgeries over the course of his or her lifetime.[7]

Because the virus usually does not show symptoms, most people who have HPV are unaware of their infection. Also, HPV can remain latent in a person’s body for a considerable amount of time. For example, some women have contracted the virus as teens and not suffered health effects from the infection until their thirties or forties. Also, when a woman gets checked for signs of HPV, the doctor’s colposcope may fail to detect genital wart infestations. Doctors may also give a woman a Pap test to see if there is any abnormal cell growth in her cervix caused by HPV.

However, this is not technically an “HPV test.” In fact, one study of more than three hundred sexually active teen girls discovered that 62 percent of the girls were infected with HPV, despite the fact that most of them had normal Pap test results![8] Because the Pap test can sometimes fail to detect HPV, many doctors recommend a yearly test for any woman who has been sexually active, even if she is now abstinent. HPV DNA tests are now available as well. Through an HPV DNA test, a woman who has HPV can know which type (or types) of the virus she is infected with. Doctors can then tell her if she is in a high or low risk category and can follow up with her accordingly.

Scientists have developed vaccines against HPV for women. Although the most common vaccine only prevents a few types of HPV, which infect only 3 percent of women,[9] those few types are responsible for causing most cases of cervical cancer and genital warts. Men can be infected with HPV as well, but because they are less likely to develop cancer from it, they are often considered “vectors” for the virus. For example, when a husband is infected with HPV, his wife is five times as likely to get cervical cancer.[10] Unfortunately, most men with HPV who get tested for STDs will not learn of their infection unless they have visible genital warts. HPV DNA testing does exist for men, but it is expensive and usually only used for research purposes.

How common is the virus among males? One way to know is to consider how quickly women are infected. According to the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 46 percent of teenage girls acquire HPV from their first sexual relationship.[11] Such high rates of infection are widely reported, and scientists now estimate that over 50 percent of sexually active men and women have been infected with one or more types of genital HPV.[12] Such high numbers seem almost unbelievable. But one must remember that most people with HPV will not show symptoms or suffer as a result of it.

Although HPV is incurable, this does not mean that it is permanent, like herpes. In fact, HPV will usually go away within a few years.[13] So despite the fact that most women have been infected with HPV,[14] only 27 percent currently test positive for the virus.[15] Young women are most at risk for HPV infection. For example, 40 percent of sexually active girls between the ages of fourteen and nineteen are currently infected with HPV. The numbers are even higher for women aged twenty to twenty-four (49 percent!).[16] Among all women, this age bracket has the highest rate of HPV.

The prevalence of HPV also varies according to marital status. For example, only 17 percent of married women are currently infected. However, nearly half of all women who are living with their boyfriends are infected with the virus.[17] One reason why the virus is so common is that HPV can spread by any genital contact (genital, oral, or by means of the hands).[18] The virus can also be present, without symptoms, on a person’s abdomen or thighs.[19] Therefore condoms are not very effective in preventing its transmission.

This is perhaps one reason why we don’t hear more about HPV. It is the Achilles’ heel of the “safe sex” campaign. For example, researchers followed hundreds of college girls without HPV and discovered that 60 percent of them contracted the virus by the end of the study. According to the researchers, “always using male condoms with a new partner was not protective [of HPV].”[20] One has to wonder if these women would have made different choices if they knew the limitations of the condom.

In the summer of 2006, The New England Journal of Medicine published a study that showed that condom use could reduce one’s risk of contracting HPV. Countless news agencies announced the discovery, and hailed it as a victory for safe sex. But most reports of the study failed to mention that the research only included 82 women, and nearly 40 percent of them contracted HPV, despite using the condom every time![21]

In order to educate the public about HPV, Congress passed Public Law 106-554. Among other things, this law required government health agencies to make sure that educational materials are “medically accurate regarding the overall effectiveness or lack of effectiveness of condoms in preventing sexually transmitted diseases, including HPV.” [22] Condom labels were to be reexamined for medical accuracy, and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) was directed to create a report that outlined the best strategies to avoid HPV.

The CDC finally published their report three years later, admitting, “The available scientific evidence is not sufficient to recommend condoms as a primary prevention strategy for the prevention of genital HPV infection.”[23] While condom use may reduce the risk of HPV-related diseases, the CDC explained earlier that “studies which have attempted to assess male condom benefit for women have generally found no evidence of protection against [HPV] infection.”[24]

Because of the inadequacy of the condom in preventing HPV, many people contract the virus while engaging in what they mistakenly believe to be “safe sex.” Senator Tom Coburn, who worked for years to encourage the FDA to correct condom labels, testified, “It is a cruel distortion of the word ‘prevention’ to tell women and young girls that the tremendous physical, emotional and financial costs of treatment for HPV infection are a cost worth bearing as a consequence of federal health agencies’ intentional distortion and cover-up of scientific data related to HPV.”[25] The financial impact he mentioned is the fact that Americans spend up to $6 billion each year treating HPV.

While some government officials have urged the FDA to update condom labels, other politicians want it left alone. Congressman Henry Waxman, a long-time opponent of abstinence education, argued, “We want to be sure that we do not end up with an unintended effect of confusing people about the situations where condoms do work. . . . [Condom labels] that include information on HPV can result in so much information on such a small package that it reduces the effectiveness of any information.”[26] Therefore, he believes that undermining the public’s confidence in the condom will have “serious public health consequences.” He added, “Are condoms perfect? Of course not. But reality requires us not to make a public health strategy against protection, but rather to ask a key question: compared to what?”[27] Unfortunately, since Waxman thinks purity is unrealistic, his only option to stop STDs is to exaggerate the effectiveness of condoms in hopes that more people will use them.

Some health “experts” concur, saying they we don’t want to “create an epidemic of panic, fear, and anxiety in adolescents and young adults who are embarking on their sexual careers.”[28] One leader in the sex ed movement tried to put an optimistic spin on the issue by saying, “I don’t think we, in any way, want to do anything that will frighten people from using condoms. . . . The bottom-line message always needs to be that most STDs are treatable.”[29] Perhaps a better bottom line message would be that all STDs are preventable by means of chastity.

The lack of clarity from government agencies has contributed to confusion within the contraception industry. For example, the makers of LifeStyles condoms issued a press release “encouraging people to have a love affair with condoms.”[30] In it, the manufacturers claimed that safe sex reduces the risk of HPV transmission. When asked for the scientific proof to back up their claim, they admitted that their public relations firm “mistakenly included HPV among the diseases for which latex condoms provide protection.”[31]

In 2005 the FDA took a step in the right direction and drafted a document with proposed language for a new condom label. As a result of this document, the commissioner of the FDA said the agency “received roughly four hundred comments on the proposed rule. Almost all comments suggested the proposed labeling language was confusing and difficult for consumers to understand. As a result, the agency intends to undertake additional labeling comprehension studies to help insure that the final labeling recommendations issued by the agency are understandable to users.”[32] While the FDA is undertaking its condom “labeling comprehension studies,” millions of people are being infected with HPV while overestimating the effectiveness of so-called “safe sex.” Click here for more information about the debate over HPV and the condom label.

__________________________

[1] F. Martinon-Torres, et al., “[Human Papillomavirus Vaccines: A New Challenge for Pediatricians],” Anales de Pediatría 65:5 (November 2006), 461–469; Helen Trottier and Eduardo L. Franco, “The Epidemiology of Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection,” Vaccine 24:S1 (March 30, 2006): S4; Division of STD Prevention, “Prevention of Genital HPV Infection and Sequelae: Report of an External Consultants’ Meeting,” Department ofHealth and Human Services (Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December, 1999), 1; Janet Torpy, “Human Papillomavirus Infection,” Journal of the American Medical Association 297:8 (February 28, 2007), 912.

[2]. M.A. Van Ranst et al., “Taxonomy of the Human Papillomaviruses,” Papillomavirus Report 3 (1993), 61–65. As reported by NIH, “Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention,” 23.

[3]. World Health Organization, “Cervical Cancer,” International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2005 (www.iarc.fr).

[4]. “Genital Skin Cancer More Deadly for Women,” HealthDay News (February 5, 2007).

[5]. L. Koutsky, “Epidemiology of Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection,” American Journal of Medicine 102:5A (May 5, 1997), 3–8.

[6]. Eloise M. Harman, “Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis,” www.emedicine.com (June 2, 2006).

[7]. Harman.

[8]. Trudee Tarkowski, et al., “Epidemiology of Human Papillomavirus Infection and Abnormal Cytologic Test Results in an Urban Adolescent Population,” Journal of Infectious Diseases 189 (January 1, 2004), 46–50.

[9]. Eileen F. Dunne, et al., “Prevalence of HPV Infection Among Females in the United States,” Journal of the American Medical Association 297:8 (February 28, 2007), 813–819.

[10]. F. Xavier Bosch, et al., “Male Sexual Behavior and Human Papillomavirus DNA: Key Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer in Spain,” Journal of the National Cancer Institute88:15 (August 1996), 1060–1067.

[11]. S. Collins, et al., “High Incidence of Cervical Human Papillomavirus Infection in Women During Their First Sexual Relationship,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 109:1 (January 2002), 96–98.

[12]. L. E. Manhart and L.A. Koutsky, “Do Condoms Prevent Genital HPV Infection, External Genital Warts, or Cervical Neoplasia?: A Meta-Analysis,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29:11 (November 2002), 725–735; Division of STD Prevention, “Prevention of Genital HPV Infection and Sequelae: Report of an External Consultants’ Meeting,” Department of Health and Human Services, 7.

[13]. A. B. Moscicki, et al., “The Natural History of Human Papillomavirus Infection As Measured by Repeated DNA Testing in Adolescent and Young Women,” The Journal of Pediatrics 132:2 (February 1998), 277–284; E. L. Franco, et al., “Epidemiology of Acquisition and Clearance of Cervical Human Papillomavirus Infection in Women from a High-Risk Area for Cervical Cancer,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases 180:5 (November 1999), 1415–1423; Ho G.Y., R. Bierman, et al., “Natural History of Cervicovaginal Papillomavirus Infection in Young Women,” The New England Journal of Medicine 338:7 (February 12, 1998), 423–428.

[14]. L. Koutsky, “Epidemiology of Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection,” The American Journal of Medicine 102:5A (May 5, 1997), 3–8, as cited in Centers for Disease Control, “Tracking the Hidden Epidemics, Trends in STDs in the United States 2000” (April 6, 2001), 18.

[15]. Dunne, et al., 815.

[16]. Dunne, et al., 816.

[17]. Dunne, et al., 813–819.

[18]. Medical Institute for Sexual Health, Sex, Condoms, and STDs: What We Now Know (Austin, TX.: Medical Institute for Sexual Health, 2002), 28; C. Sonnex, S. Strauss, and J. J. Gary, “Detection of Human Papillomavirus DNA on the Fingers of Patients with Genital Warts,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 7:5 (1999): 317–319; R. Winer, et al., “Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection: Incidence and Risk Factors in a Cohort of Female University Students,” American Journal of Epidemiology 157:3 (February 1, 2003), 218–226; Hammarstedt, et al., “Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for the increase in incidence of tonsillar cancer,” International Journal of Cancer 119:11 (December, 2006): 2620-2623.

[19]. NIH, “Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention,” 26; House of Representatives, “Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act of 1999” (November 22, 1999), 10.

[20]. R. Winer, et al., “Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection: Incidence and Risk Factors in a Cohort of Female University Students,” American Journal of Epidemiology157:3 (February 1, 2003), 218.

[21]. R. Winer, et al., “Condom Use and the Risk of Genital Human Paillomavirus Infection in Young Women,” The New England Journal of Medicine 354:25 (2006), 2645–2654.

[22]. Public Law 106–554, 106th Congress, 114 Stat. 2763 (December 21, 2000).

[23]. Julie Louise Gerberding, “Report to Congress: Prevention of Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services (June 2004), 4–5.

[24]. Division of STD Prevention, “Prevention of Genital HPV Infection and Sequelae: Report of an External Consultants’ Meeting,” Department of Health and Human Services, 14.

[25]. Tom Coburn, “Cervical Cancer and Human Papillomavirus,” Hearing before the Subcommittee on Criminal Justice, Drug Policy and Human Resources, U.S. House of Representatives (March 11, 2004), 4.

[26]. Ilka Couto and Cynthia Dailard, “Wanted: A Balanced Policy and Program Response to HPV and Cervical Cancer,” The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy 2:6 (December 1999).

[27]. Lara Jakes Jordan, “Condom Warning Labels Mulled,” cbsnews.com, Associated Press, Washington (March 12, 2004).

[28]. Audio transcript, “Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness and STD Prevention,” National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (June 12–13, 2000).

[29]. Tamara Kerinin, as quoted by Cheryl Wetzstein, “Agencies Rapped for Shirking HPV Law,” Washington Times (December 23, 2003).

[30]. LifeStyles Condoms, press release, Ansell Healthcare, Inc. (July 31, 2000).

[31]. Letter from Kerry A. Hoffman, Regional Director, Ansell Healthcare, Inc. (September 8, 2000).

[32]. “Latest News: Andrew C. Von Eschenbach, M.D., Confirmation, Questions for the Record,” Abstinence Clearinghouse E-mail Update (September 9, 2006), reply to Question 14.

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is a rare STD caused by a type of Chlamydia. It can scar the genitals and colon, and can swell and burst the lymph glands. LGV has been more common in Southeast Asia and Africa, but because of an increased number of cases appearing in Europe and America, health professionals are concerned. Men are more commonly infected than women, and those reporting homosexual activity are more likely to contract the STD than heterosexuals. The disease is treatable, by means of a three week course of antibiotics.

Trichomoniasis is a protozoan parasite that infects the genital tract. In North America it infects about eight million people each year. Worldwide the annual total is 170 million. According to the CDC, it is the most common curable STD among young women.[1]

However, most people who are infected with trichomoniasis do not have symptoms, especially males. When symptoms are present, they may include genital irritation and burning with urination. For women the parasite can cause vaginitis, cervicitis, abnormal bleeding, swelling, itching, discharge, abdominal pain, and other symptoms. When a woman is infected with trichomoniasis, she is also more susceptible to contracting HIV, if exposed.[2] Although uncommon, an infected mother can pass the parasite on to her baby through childbirth. If she is infected while pregnant, the baby also has an increased risk of being born early and having low birth weight.

In regard to condom effectiveness in preventing the spread of trichomoniasis, the National Institutes of Health reported, “One limited study demonstrated a 30 percent protective effect for women. The [lack] of epidemiologic studies on condom effectiveness for trichomoniasis does not allow an accurate assessment of the reduction in risk of trichomoniasis offered by condom usage.”[3]

____________________

[1]. Centers for Disease Control, “Trichomoniasis,” fact sheet (May 2004).

[2]. F. Sorvillo, et al., “Trichomonas Vaginalis, HIV, and African-Americans,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 7:6 (November/December 2001), 927–932; J.R. Schwebke, “Update of Trichomoniasis,” Sexually Transmitted Infections 78:5 (2002), 378–379; Centers for Disease Control, “Trichomoniasis,” fact sheet.

[3]. National Institutes of Health, “Workshop Summary: Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention.”

This depends on what you mean by “most common.”

The most commonly transmitted STD is HPV. According a study published in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 46 percent of teenage girls acquire HPV from their first sexual relationship.[1] Such high rates of infection are widely reported, and scientists estimate that over 50 percent of sexually active men and women have been infected with one or more types of genital HPV.[2] Young women are most at risk of being infected. For example, 40 percent of sexually active girls between the ages of fourteen and nineteen are currently infected with HPV. The numbers are even higher for women aged twenty to twenty-four (49 percent)![3] Among all women, this age bracket has the highest rate of HPV. The prevalence of HPV also varies according to marital status. For example, only seventeen percent of married women are currently infected. However, nearly half of all women who are living with their boyfriends are infected with the virus.[4] Such high numbers seem almost unbelievable. But one must remember that most people with HPV will not show symptoms or suffer significantly as a result of it. Although HPV is incurable, this does not mean that it is permanent. In fact, HPV will usually go away within two years.[5] So despite the fact that most women have been infected with HPV,[6] only 27 percent currently test positive for the virus.[7]

The most common STD in terms of current infections (prevalence) is herpes (HSV). About one in six people are infected with genital herpes type-2.[8] Among sexually active singles, the percentage of those infected with herpes is even higher: between 30 and 40 percent![9] While these numbers may seem astoundingly high, one must realize that nine out of ten people who have genital herpes are unaware that they are infected.[10] Despite the fact that more people contract HPV than Herpes, Herpes is more common because it is permanent.

The most common reportable STD is chalmydia, because doctors don’t have to report diseases such as HPV, Herpes, and many others. In 2005 nearly a million cases were reported, but most cases go undiagnosed, and so the Centers for Disease Control estimate that about three million infections occur each year in the United States.[11].

___________________________________

[1]. S. Collins, et al., “High Incidence of Cervical Human Papillomavirus Infection in Women During Their First Sexual Relationship,” BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 109:1 (January 2002): 96-98.

[2]. L.E. Manhart and L.A. Koutsky, “Do Condoms Prevent Genital HPV Infection, External Genital Warts, or Cervical Neoplasia?: A Meta-Analysis,” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 29:11 (November 2002): 725-735; Division of STD Prevention “Prevention of Genital HPV Infection and Sequelae: Report of an External Consultants’ Meeting,” DHHS, (CDC), 7.

[3]. Eileen F. Dunne, et al., “Prevalence of HPV Infection Among Females in the United States,” The Journal of the American Medical Association 297:8 (28 February 2007): 816.

[4]. Dunne, et al., 813-819.

[5]. A.B. Moscicki, et al., “The Natural History of Human Papillomavirus Infection as Measured by Repeated DNA Testing in Adolescent and Young Women,” The Journal of Pediatrics 132:2 (February 1998): 277-284; E.L. Franco, et al., “Epidemiology of Acquisition and Clearance of Cervical Human Papillomavirus Infection in Women from a High-Risk Area for Cervical Cancer,” The Journal of Infectious Diseases 180:5 (November 1999): 1415-1423.

[6]. L. Koutsky, “Epidemiology of Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection,” The American Journal of Medicine 102:5A (5 May 1997): 38, as cited in Centers for Disease Control, “Tracking the Hidden Epidemics, Trends in STDs in the United States 2000,” (6 April 2001), 18.

[7]. Dunne, et al., 815.

[8]. Fujie Xu, et al., “Trends in Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and Type 2 Seroprevalence in the United States,” The Journal of the American Medical Association 296:8 (August 2006): 964-973.

[9]. Joe McIlhaney, M.D., Safe Sex (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker House Books, 1992), 100.

[10]. D.T. Fleming, et al., “Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 in the United States, 1976 to 1994,” New England Journal of Medicine 337 (16 October 1997): 1105-1111; P. Leone, “Type-specific Serologic Testing for Herpes Simplex Virus-2,” Current Infectious Disease Reports 5:2 (April 2003):159-165.

[11]. Division of STD Prevention, “Trends in Reportable Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the United States, 2005,” (CDC), 1.

In June 2006, the FDA approved a vaccine that prevents four types of human papillomavirus (HPV) in women. The injection is known as Gardasil, which is an abbreviation of “guard against squamous intraepithelial lesions.” When a woman receives Gardasil, she must receive an initial injection, followed by another shot in two months, and a final dose at six months. This completes the vaccination process, which costs about $360. The FDA has also approved the use of Gardasil in males aged 9 to 26 years.

In October 2009, the FDA approved the use of another HPV vaccine, Cervarix, in females aged 10 to 25 years. This vaccine only targets two strains of HPV (16 and 18), and therefore reduces the risk of cervical cancer, but not genital warts.

The makers of Gardasil are planning to release a new HPV vaccine, known as V503, which will target nine strains of the virus, instead of only four.

There are more than 100 different types (strains) of HPV, and about 40 of these cause genital infections. Of those 40, about half can cause cancer, and some can cause genital warts. The four types of the virus that Gardasil prevents cause 90 percent of genital warts (types 6 and 11) and 70 percent of cervical cancer (types 16 and 18) [1]. So, even though the vaccine only targets a few strains of the virus, those few strains are responsible for causing most cases of cervical cancer and genital warts.

Some mistakenly believe that the vaccine prevents 70 percent of HPV. This is not true. Others mistakenly believe that the vaccine is only 70 percent effective. This, also, is not true. The vaccine is extremely effective, but only as it relates to preventing those four types of the virus. While the vaccine may prevent two cancer-causing strains of HPV, an article in The New England Journal of Medicine pointed out that blocking these strains of the virus may allow other cancerous HPV strains to fill the void [2]. If this happens, the overall decrease in cervical cancer would be reduced.

According to The Journal of the American Medical Association, 27 percent of women between the ages of 14 and 49 are currently infected with HPV. However, only 3.4 percent are infected with the strains of the virus covered by Gardasil [3].

Safety Concerns

According to Merck, the drug maker of Gardasil, clinical trials have demonstrated the vaccine to be both safe and effective. Common side effects of the drug include pain at the injection site, swelling, fever, nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, and dizziness. However, concerned women and parents who Google “lawsuit” and “Gardasil” are often taken aback by how many organizations doubt the drug’s safety and how many lawsuits have been filed against Merck because of the drug.

Since the vaccine is new, the long-term side effects have yet to be determined. Hopefully, serious effects of the drug will be rare, improvements will be made, and it will prove to be an effective help in decreasing rates of cervical cancer worldwide, which takes the lives of about 288,000 women annually [4].

Mandating the vaccine

Because Gardasil has been approved for use in women aged 9-26, there has been much debate over whether or not states should mandate the vaccine. Many government officials have opposed such a mandate, partly because the drug only went through three and a half years of testing [5]. The director of the National Institutes of Health added, “We don’t know what the long-term effects of Gardasil are because it’s too early, so I would say to walk before you run. . . . You have to understand that in public health, what the doctor says is not always the only thing that counts”[6].

Another reason why legislators are hesitant to mandate the drug is because HPV is not a contagious disease, like measles, that could be easily transmitted from student to student. Since it is a sexually transmitted disease, its transmission depends upon one’s behavior. In fact, the number one risk factor for genital HPV infection is one’s number of lifetime sexual partners [7].

While the CDC recommends routine use of the vaccine for adolescent females, Dr. Jon Abramson, chairman of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) said that lawmakers should not make the vaccination mandatory, and that Merck should not lobby the state governments to require it for school attendance [8]. Likewise, the chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on infectious disease does not support making the vaccine mandatory. “I think it’s too early,” he said. “This is a new vaccine. It would be wise to wait until we have additional information about the safety of the vaccine” [9].