Intrauterine Device (IUD) & Intrauterine System (IUS)

The Intrauterine Device is a T-shaped device inserted into the woman’s uterus. Although it is not the most common contraceptive in America, it is the world’s most widely used form of reversible birth control.[1] There have been several different kinds of IUDs, but only two are currently approved for use in the United States, ParaGard and Mirena.

Before ParaGard was introduced in the 1980s, millions of women had used other kinds of IUDs. One popular version in the 1970s was called the Dalkon Shield, which was owned by a company that also made flea collars and press-on nails.[2] The Dalkon Shield was a thumbnail-sized plastic device with a string dangling below it that could be used to remove it from a woman’s uterus.

In order to demonstrate its safety and effectiveness, a doctor from Johns Hopkins Medical School tested the product on over six hundred women. However, this doctor later admitted that the studies were intentionally skewed, and that he had a conflict of interest: he received a percentage of the profits on its sales.[3] Its manufacturers vehemently defended the safety of the product and began marketing it in 1971, wildly exaggerating its effectiveness.

Not surprisingly, it didn’t take long for complaints to surface. Six weeks after sales of the Shield began, a doctor wrote to the manufacturer, “I have just inserted my tenth Dalkon Shield and have found the procedure to be the most traumatic manipulation ever perpetrated upon womanhood. . . . I have ordered all Shields out of my office and will do the same in all clinics with which I am affiliated.”[4] Health experts requested that the IUD be taken off the market, but the company, A.H. Robins, refused to halt distribution, saying that such a move would “be a ‘confession of liability,’ and Robins would lose many of the pending lawsuits.”[5] Thankfully the FDA prevailed in 1974, and the IUD was taken off the market.

Hundreds of thousands of women experienced injury from using the Dalkon Shield. Part of the problem was that the string that dangled beneath the device acted as a wick for bacteria to ascend into a woman’s uterus. Injuries included life-threatening pelvic infections, hospitalization, sterility, hysterectomy, and babies born with cerebral palsy, blindness, and mental retardation. At least twenty deaths were also reported,[6] not including the thousands of babies who were miscarried or stillborn.[7]

A few years before the contraceptive was yanked off the shelves, the manufacturers knew that their U.S. market would be dwindling. So they started “dumping.” This means that they began selling mass quantities of the device at wholesale prices to developing nations through a government organization, the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID). Groups that worked with AID, such as Planned Parenthood, distributed hundreds of thousands of Dalkon Shields to women across the globe.[8] However, when the makers of the device were forced to take their product off the market in the United States, AID had to issue an international recall. Unfortunately, the product continued to be used in many countries.[9]

Because of the lawsuits that began to pile up, the maker of the Dalkon Shield asked all doctors to remove any remaining ones from their patients. But the warning came too late: victims of the product were seeking justice, and over $12 billion in lawsuits were filed.[10] By the mid-1980s A.H. Robins filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, because more than 327,000 women filed injury claims against the company.[11] During the legal battles it was discovered that A.H. Robins knew that their contraceptive could cause life-threatening infections but withheld and even destroyed some of the evidence.[12] One Chief U.S. district judge, who heard over four hundred cases against the Shield in Minnesota, reprimanded the corporate leaders of the drug company and said he hoped that his statement “burns its mark into your souls.”[13]

One New York woman who was accidentally sterilized for life by the Dalkon Shield recalled receiving it from Planned Parenthood as a college student. She sued and later reported in The New York Times, “I won the arbitration. But the victory doesn’t help when we look at friends with their children and wonder what our own kids would have been like.”[14] Since the drug was distributed in over eighty countries to an estimated 4.5 million women, the majority of women who suffered from the Dalkon Shield never will have had the chance to seek compensation for their pain and loss.

Because the IUD has such a sordid past, it has not been popular among American women. In the 1980s most IUD manufactures quit marketing their products in the United States because of the rising cost of lawsuits and the decreased interest in the products.[15]

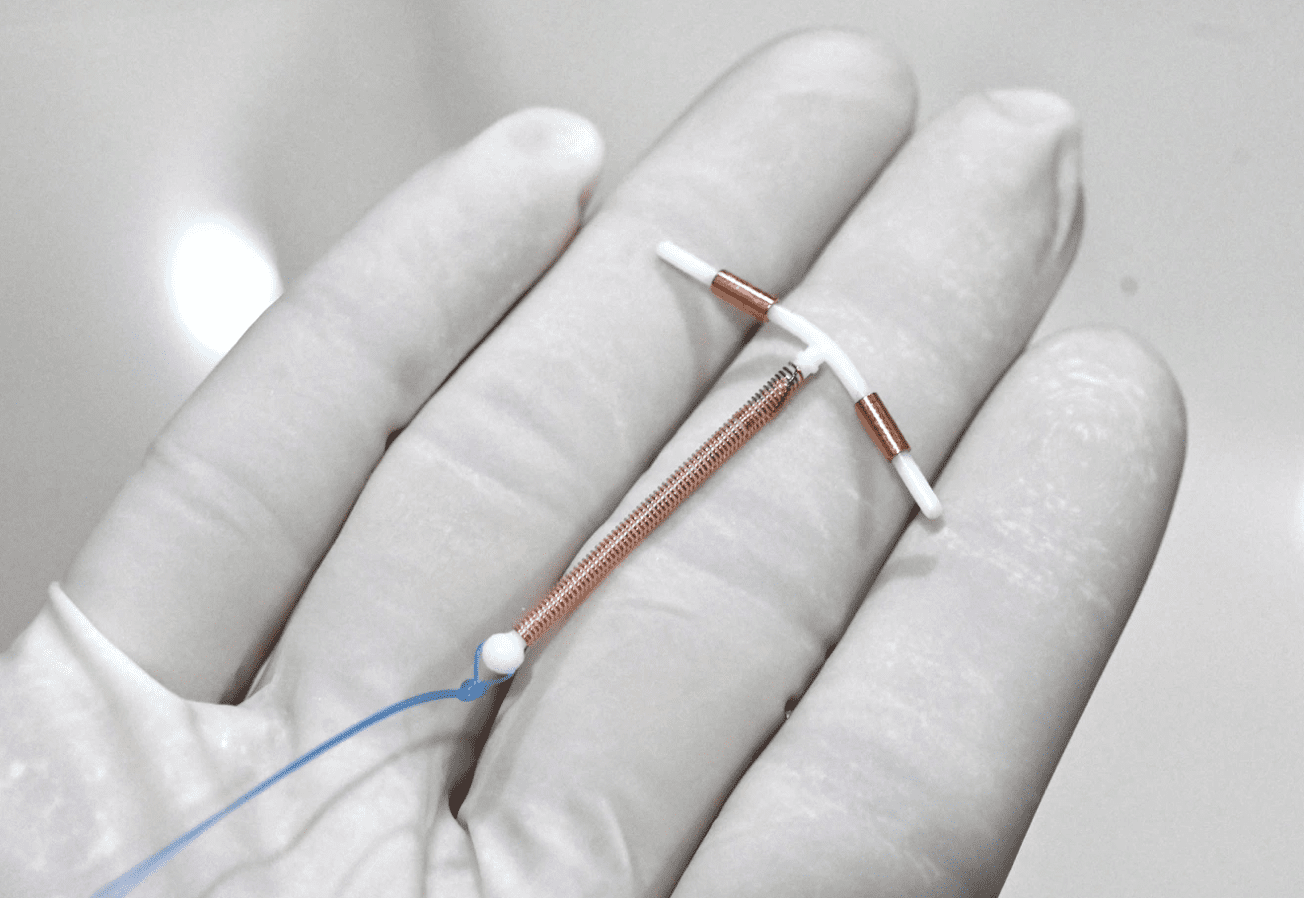

However, in 1984 a new IUD was approved by the FDA, ParaGard. This contraceptive is a T-shaped piece of white plastic (polyethylene) wrapped with a copper wire. It irritates the lining of the uterus, causing it to release leukocytes and prostaglandins that are toxic to the sperm and egg. This reduces the chances of fertilization. However, it does not stop the woman from ovulating. Should conception occur, the IUD can also act as an abortifacient by keeping a newly conceived baby from implanting in the womb.[16] For this reason some women have used the IUD as a form of “emergency contraception” up to five days after intercourse.

ParaGard is estimated to be more than 99 percent effective, and it is safer than the Dalkon Shield. However, it is not without its own risks. According to the patient package insert for ParaGard, if a woman becomes pregnant while using it, “you may get a severe infection or shock, have a miscarriage or premature labor and delivery, or even die. Because of these risks, your healthcare provider will recommend that you have ParaGard removed, even though removal may cause miscarriage.”[17] Other possible side effects include pelvic inflammatory disease (which can lead to infertility, hysterectomy, or even death), dizziness, nausea, ectopic pregnancy, anemia, backache, cramps, allergic reaction, perforation of the uterus (causing infection, scarring, and damage to other organs, possibly requiring surgery to repair), and so on.[18]

The ParaGard IUD can remain in a woman for up to ten years, and a healthcare professional can remove it before then if the woman wishes. However, sometimes the device gets stuck in the woman, requiring surgical removal. Despite the possible side effects, sales of ParaGard in 2004 totaled approximately $48 million.[19]

The difference between an IUD and an IUS (Intrauterine System) is that the IUS releases hormones, and the IUD does not. The first IUD with hormones was known as Progestasert, but this was manufactured only until 2001. Now the only version available is known as Mirena, which releases a hormone called levonorgestrel into the uterus. The T-shaped device is placed in a woman’s uterus and can be left there for up to five years.

According to its maker, “there is no single explanation of how Mirena works. It may stop release of your egg from your ovary, but this is not the way it works in most cases. It may block sperm from reaching or fertilizing your egg. It may make the lining of your uterus thin. We do not know which of these actions is most important for preventing pregnancy and most likely all of them work together.”[20] Therefore, Mirena can prevent pregnancy and may also act as an abortifacient (by changing the uterine lining and failing to stop ovulation).

Possible side effects or complications may include ectopic pregnancy, life-threatening infection, irregular bleeding, missed periods or a cessation of periods, pelvic inflammatory disease (which can lead to infertility, hysterectomy, or death), perforation of the uterus (which can cause internal scarring, infection or damage to other organs), severe cramping, dizziness, fainting, yellowing of the eyes or skin, ovarian cysts, stroke, and heart attack.[21]

Compared to reversible forms of contraception, Mirena is highly effective in preventing pregnancy (over 99 percent). However, if a woman becomes pregnant while using Mirena, she may experience severe infection, premature delivery, and even death. The doctor may attempt to remove Mirena, although this may cause a miscarriage.[22]

When a woman uses Mirena while breast-feeding, some of the hormones pass through the breast milk to the baby. Existing studies do not show any adverse side effects, but the World Health Organization notes, “there are no data evaluating the effects of progestogen exposure via breast milk on brain and liver development.”[23]

Not surprisingly, Mirena was used for years on millions of women in other countries before it was approved by the FDA in 2001. Just one year later, in the U.S. alone it raked in $36 million for its makers, and sales have continued to soar.[24]

The IUD has often been touted as one of the best ways to reduce rates of abortion because of its effectiveness in preventing pregnancy. However, according to research conducted by the nation’s largest abortion provider, Planned Parenthood, the number of women who had abortions after becoming pregnant while on an IUD between 2000 (when Mirena was released) and 2014, increased by more than 450% (from 1700 to 7700).[25]

_______________________

[1]. U.N. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “World Contraceptive Use, 2005.”

[2]. Michele Kort, “Fatal Contraption: The Horrifying Truth about the Dalkon Shield,” Essence (July 1989).

[3]. “The Dalkon Shield Story: A Company Rewarded for its Faulty Product—

A.H. Robins Company, Inc. Lawsuit,” Healthfacts, May 1996.

[4]. Russell Mokhiber, “The Dalkon Shield: A Deadly Product from A.H. Robins, Multinational Monitor 8:4 (April 1987).

[5]. Morton Mintz, “A Crime Against Women,” Multinational Monitor 7:1 (January 15, 1986).

[6]. Hicks, Karen M., Surviving the Dalkon Shield IUD: Women v. The Pharmaceutical Industry (New York: Teachers College Press, 1994), 2.

[7]. Mokhiber, “The Dalkon Shield”; Mintz, “A Crime Against Women.”

[8]. International Planned Parenthood Federation, “The Dalkon Shield IUD,” IPPF Medical Bulletin 14:6 (December 1980), 3.

[9]. Barbara Ehrenreich, “The Charge: Genocide,” Mother Jones (November/ December 1979).

[10]. Mintz, “A Crime Against Women.”

[11]. Hicks, 6.

[12]. “The Dalkon Shield Story,” Healthfacts.

[13]. Mokhiber, “The Dalkon Shield.”

[14]. Meryl Gordon, “A Cash Settlement, but No Apology,” The New York Times (February 20, 1999).

[15]. Baylor College of Medicine, “Evolution and Revolution: The Past, Present, and Future of Contraception,” The Contraception Report 10:6 (February 2000), 18.

[16]. ParaGard Patient Package Information, Duramed Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (May 2006); J. B. Stanford and R.T. Mikolajczyk, “Mechanisms of Action of Intrauterine Devices: Update and Estimation of Postfertilization Effects,” American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 187:6 (December 2002), 1699–1708; Y.C. Smart, et al., “Early Pregnancy Factor as a Monitor for Fertilization in Women Wearing Intrauterine Devices,” Fertility and Sterility 37:2 (February 1982), 201–204.

[17]. ParaGard Patient Package Information.

[18]. ParaGard Patient Package Information.

[19]. “Barr to Acquire FEI Women’s Health,” Breaking News From Pharma & Bio Ingredients, November 18, 2005 (www.pharmabioingredients.com).

[20]. Mirena Patient Information Booklet, Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (2004), 9.

[21]. Mirena Patient Information Booklet; K. Van Houdenhouven, et al., “Uterine Perforation in Women Using a Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine System,” Contraception73:3 (2006), 257–260.

[22]. Mirena Patient Information Booklet, 10.

[23]. “Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use,” World Health Organization, Third Edition, 2004.

[24]. Aude Lagorce, “Schering AG Storms Birth Control Market,” forbes.com (July 11, 2003).

[25]. Rachel Jones, “Reported contraceptive use in the month of becoming pregnant among U.S. abortion patients in 2000 and 2014,” Contraception 97 (2018) 309–312.